We’re going to dive into the deep end on the first post here, and explain some of what we do differently here at Quint. Our first book being prepared is Mark Twain’s The Innocents Abroad, which was published in 1869. It might be surprising to many that this book, which many people have never heard of, was Twain’s most popular book during his lifetime. Today we think primarily of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, or other novels like The Prince and the Pauper or A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, but Twain wrote five travel books, of which The Innocents Abroad was his first. This is the book that made Twain famous, and for a number of reasons it is the first book we’ve chosen to come out with in our Essentials edition.

Spelling

English spelling, particularly in the United States, was in a period of flux during Twain’s life. There were many efforts to standardize English spelling during the 19th century, particularly American English spelling. Noah Webster, of dictionary fame, was actually most famous during his lifetime for what was referred to as the Blue-Backed Speller, introduced in 1783. The Speller, used by schoolchildren, evolved over time and changed many spellings, including:

- preferring -er to -re (theater, not theatre)

- using s instead of c (ecstasy, not ecstacy)

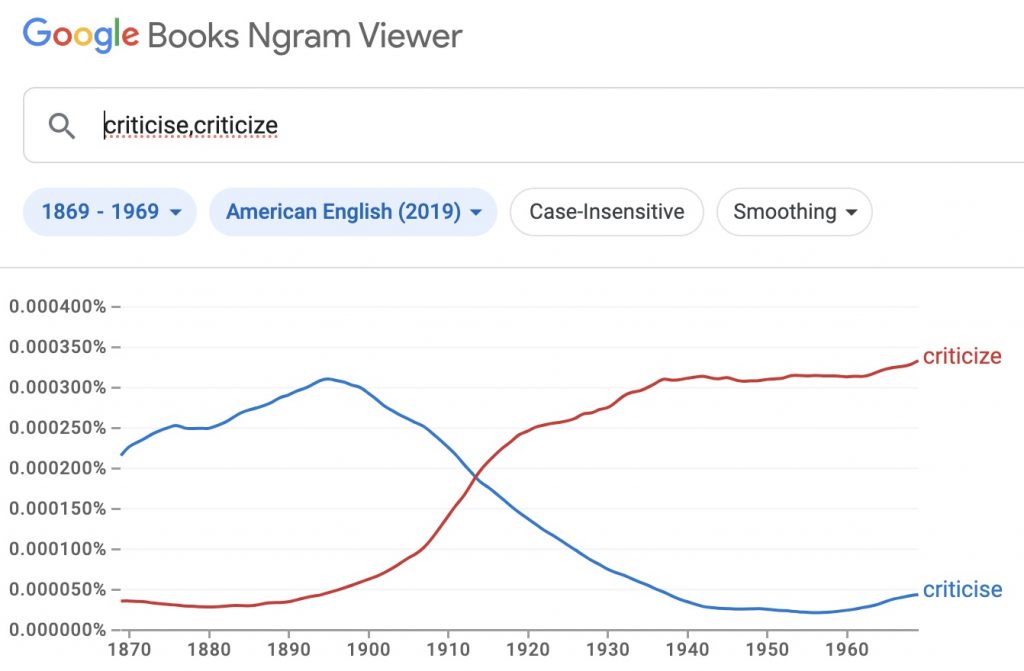

- using z instead of s (criticize, not criticise)

- using o instead of ou (color, not colour)

In the first hundred years or so the speller sold over 60 million copies. However, the influence of British literature during the same time was very strong, and multiple spellings were used commonly. Twain himself used many spellings that today are primarily used in England. Some spellings would today not be used on either side of the Atlantic. Some words that show up in The Innocents Abroad include ecstacy, theatre, irruption, trowsers, staid, unclassable, indorse, lettred, and divers. Here at Quint we believe in preserving the historic usage of words, but where necessary we add explanatory notes. However, while spelling differences are usually easy to understand, many words used in 1869 are simply not in usage today.

Archaic and other unknown words

Many of the words Twain used were common at the time, but are almost completely unknown to the average reader today. Some words are no longer used, and some are used in different ways.

Some words are for things that no longer exist, or at least are not in common use. How many people today know what a boot-jack is? or a dead-light? or a horse-pistol? or a zampillaerostation?

Sometimes multiple words were in use for the same thing at the time, but one word won out since then, such as a cameleopard, now called only a giraffe.

Some words had meanings then that we no longer use, such as a diligence being a public stagecoach that followed a set route, similar to what might be a public bus today.

Places also had different names at the time. Constantinople is today’s Istanbul. Smyrna is today’s Izmir. Leghorn is now mostly known as Livorno. When traveling to the holy land, Twain called places by the names they were known as in the bible, not necessarily what they were called at the time. In fact Twain very much makes fun of the fact that neither he nor his traveling companions could remember the actual names of the places he visited, and that they would sometimes assign easier to remember names.

So part of what we want to provide the reader of our books is broad historical and linguistic context. Not everyone needs all the notes, but many readers, no matter how well read they are, will need some.

Using technology, both old and new

There are a number of ways to work out the definitions of archaic words in a text. One way is to simply look the words up in a dictionary. For usages that are not common today, looking them up in a 19th century dictionary is helpful. Alternatively one can look in a historical dictionary such as the OED. Many older dictionaries are searchable online, such as Johnson’s (1775), Webster’s (1828), the Century Dictionary (1889), and Webster’s Revised Unabridged (1913). Some web sites consolidate multiple dictionaries, along with other features, such as Wordnik.

Dictionaries were in many ways, advanced technology of their day. They offered a much easier way to accomplish a task than was previously possible. Creating dictionaries, or even an in-book lexicon, is a lot of work. Defining words usually starts with finding many usages of the word, and separating them into difference senses, and then creating definitions based on the actual usage. The OED famously started in the 19th century by having people mail in usages of words they found in books. Those usages were transcribed onto cards, and collected in physical filing systems, and then used when the definitions for those words were being written. Today the technology has come a long way, but the methods are still based on the same principles. Today large collection of text are combined into electronic corpuses, which can be quickly searched and analyzed to find the usages of words. One can analyze the words used by an author by building a corpus of just their works. This allows you to see examples of how that specific author used words, which may be easier to understand when seeing the words used in multiple publications.

Take an example from Innocents Abroad, the word tabu. Tabu is simply an alternate spelling of a word we use today, taboo. Here’s a look at Twain’s use of the word in his primary works:

Using an application called AntConc, we’ve build a corpus of Twain’s main works. Searching for the word tabu, we see it show up 28 times. It is only once in The Innocents Abroad (1869), 15 times in Roughing It (1872), and 12 times in Following the Equator (1897). We can see in number 23, that Twain defines the term (in a footnote). Number 12 is also interesting because he explains the effectiveness of having a tabu in a society:

“The tabu was the most ingenious and effective of all the inventions that has ever been devised for keeping a people’s privileges satisfactorily restricted.”

Let’s say you also want to see the words usage in a wider context. You could build bigger and bigger corpuses, or you could use various online corpuses. One useful site is Wordnik, which as mentioned above has multiple searchable dictionaries, but also shows examples of usage it has collected from a wide variety of literary and online works. Here are two of the results it displays for tabu:

The first quote is the same one we found above. There are two things interesting about the second quote. First, the book is written about the same areas that Twain himself was writing about at that time. He worked for California papers, and travelled to the Sandwich Islands (now known as Hawaii) and wrote about it. I don’t know if Twain knew the author of that book, but it seems likely he read the book, as the two quotes look awfully similar. Twain wrote his book thirty two years after Nordhoff wrote his, so maybe the similar language was not intentional, just a long-ago line in his memory that he didn’t realize he had picked up from another book.

Back to Spelling

One interesting thing we can look at with Mark Twain, when considering his spelling, is changes made in an authorized uniform edition that was published in 1899. The Innocents Abroad was widely printed from 1869, but was not changed during that thirty year period. However, in 1899 Twain published a collection of all his major works, in which minor revisions were made for the first time. The most obvious change to the book was that it was split into two volumes. Changes were made in the usage of parenthesis and commas. The original edition did things like, (text inside parenthesis,) which is similar to the usage of commas inside quotes, but looks very odd today. In the 1899 edition that was changed. As mentioned above, there are many words we spell differently today. Some of those changes were made in the 1899 edition, such as:

| 1869 Spelling | 1899 Spelling |

|---|---|

| ancle | ankle |

| centre | center |

| esctacy | esctasy |

| irruption | eruption |

| lettred | lettered |

| lustre | luster |

| meagre | meager |

| plough | plow |

| pretence | pretense |

| sceptre | scepter |

| staid | stayed |

| theatre | theater |

| woollen | woolen |

One can clearly see some of the changes in the speller showing up here. Words ending in -re switching to -er, and instances of c switching to s (and k). However, not all words were changed. Here are some words that remained the same in the 1899 edition as they were in the 1869 edition:

| Original Spelling | Modern American Spelling |

|---|---|

| chequered | checkered |

| criticise | criticize |

| divers | diverse |

| drouth | drought |

| hath | has |

| inclose | enclose |

| incumber | encumber |

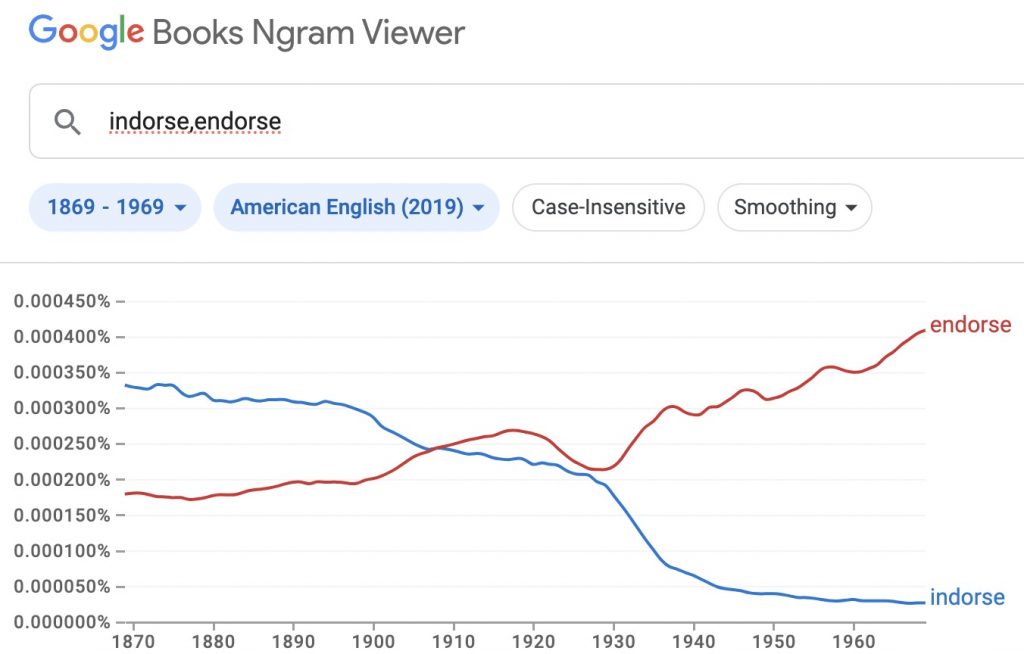

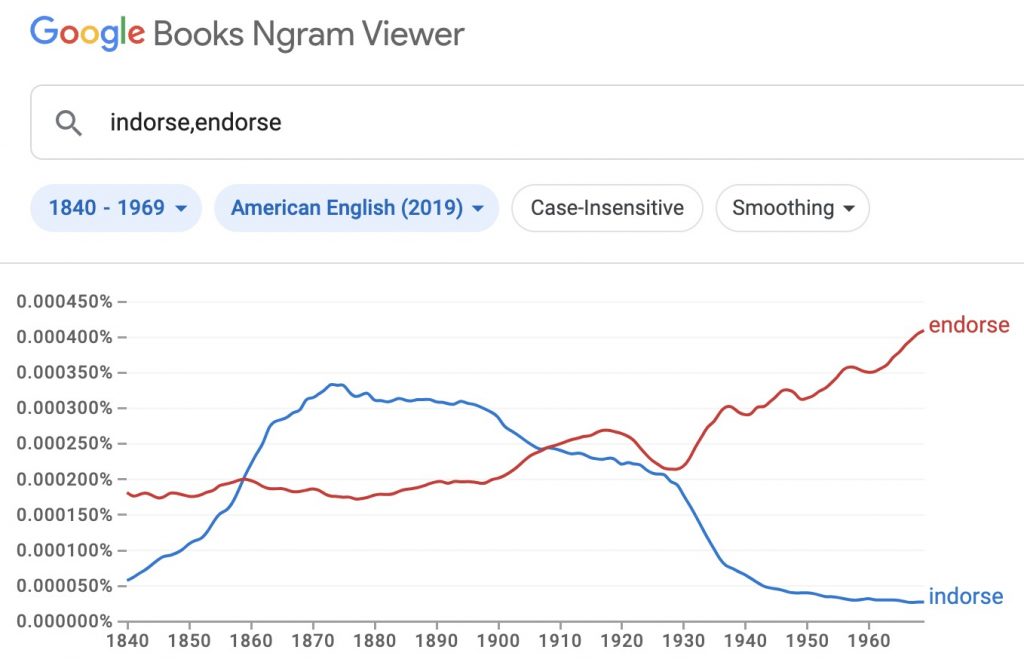

| indorse | endorse |

| trowsers | trousers |

One might argue that some of these were stylistic choices that Twain made. Twain’s use of hath, for example, is largely stylistic. Some of these spellings may have still been commonly used at the time.

Google has a useful tool based on Google Books, called the Google Books Ngram Viewer. You can give it a series of words, choose a year range, and also choose if you only want American English, or one of many other collections of texts. Here are the words criticise and criticize, showing usage from 1869 to 1969:

You can clearly see that in 1899 criticise was still much more in use, but in about 1913, the usages crossed, and the z spelling rose and the s spelling dropped.

Here’s another example, with indorse and endorse:

It follows a similar pattern, with the inflection point in 1908. However, if you expand it back a few more years you can see how complex the evolution of spelling was in America:

Indorse was once much less popular than endorse, but passed endorse in usage about 1858 and peaked just after the publication of The Innocents Abroad. Endorse kept a pretty steady usage the whole time, and it wasn’t until the late 1920s that the use of endorse shot up while indorse dropped quickly.

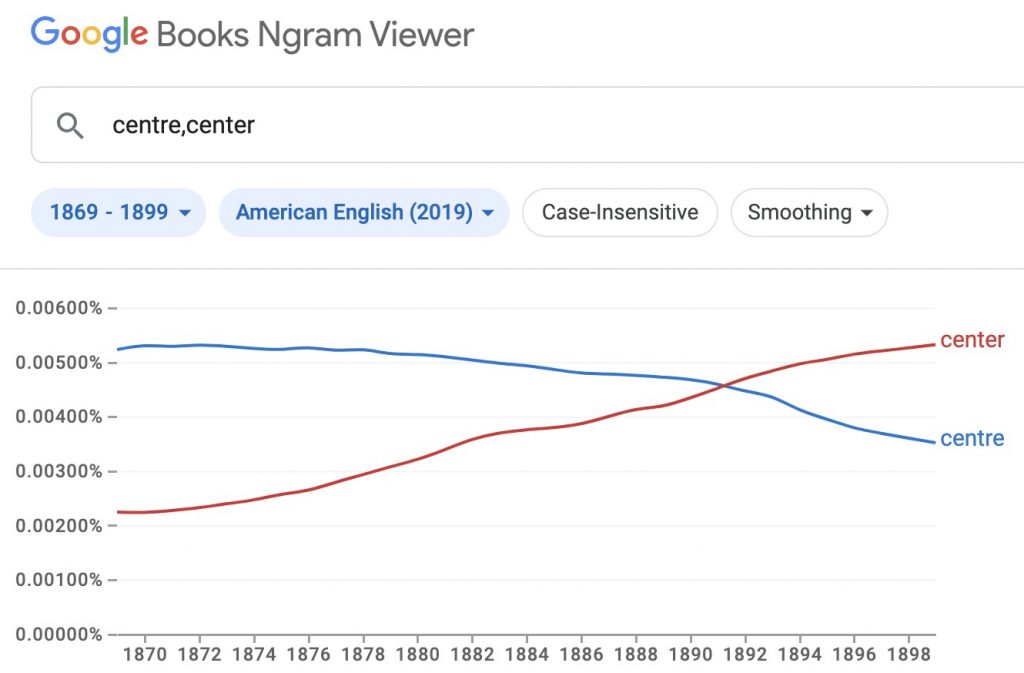

One last ngram view, using one of the words that was changed in the 1899 edition:

Here you can see the usage of centre and center between the years of publication of the two editions (1869-1899). The inflection point is roughly 1891. So unlike the above examples whose inflection points came after 1899, here is an example where the inflection point occurred before 1899, and the word was indeed changed.

So how does all of this affect a new edition of The Innocents Abroad? Wait and see.

Leave a Reply